Sarah Logie FWCF, delves into one amazing element of the horse

The importance of healthy feet is well recognised for the soundness of our equines but, appreciation should also be given to the joints further up the limb. This piece aims to cover the anatomy, structure and function of one of the hardest working joints in the limb – the fetlock.

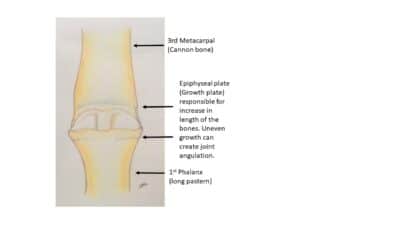

The fetlock joint consists of the distal end of the third metacarpal (cannon bone) the proximal end of the first phalanx (long pastern) and the two proximal sesamoid bones.(Figure 1).

It is classified as a synovial ginglymus joint. This means a hinge joint with a joint capsule, containing lubricating synovial fluid. This fluid not only lubricates the joint but nourishes the articular cartilage within it.

The bones are held together by a large number of ligaments – required due to the extreme forces that pass through the joint. The joint is stabilised by collateral ligaments (Figure 2) on the medial and lateral aspect of the joint.

A number of ligaments hold the sesamoid bones in place to prevent them being forced up the leg during loading (Figure 3). Most superficially (closest to the surface) annular ligaments wrap around all the soft tissue that pass over the joint – holding all the tissues in their respective places throughout the full range of motion.

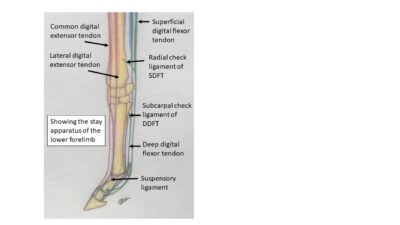

The largest ligament associated with the joint is the suspensory ligament, which ‘suspends’ (Figure 4) the weight of the horse and is a major part of the stay apparatus – the system of ligaments and tendons that allow the horse to sleep standing up while using minimal muscular energy (Figure 5).

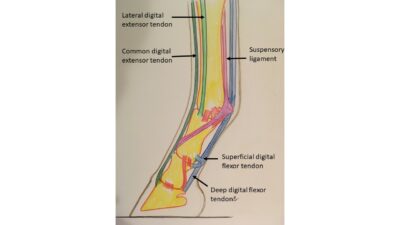

The tendons associated with the joint are the extensor tendons found at the front (dorsal) of the limb and, the flexor tendons found on the back (palmar) of the limb (Figure 6). The flexor tendons also help support the fetlock during weight bearing – particularly the superficial digital flexor tendon (SDFT) due to its insertion points being just distal to the joint.

During locomotion the structure of the tendons means they act as a kinetic energy store; storing energy as they are loaded and stretched slightly and then aiding forward motion by releasing that energy, when the weight starts to move forward. The horse’s limbs are long efficient levers allowing it to perform at the athletic levels we see in all the equine disciplines.

When observing the horse moving, the joint’s huge range of motion (ROM approximately 140°) can be seen. It moves from fully flexed, as seen when a jumper tucks its front feet in as it passes over a pole, to full extension on landing where the joint may be seen to impact the ground.

At this point the horse is taking its entire bodyweight down this one limb and into this single joint and foot. Any irregularity or defect is going to become aggravated and potentially create lameness. Development and conformation In young growing horses it is accepted that the angulation (in the medial/lateral plane) can no longer be changed once the animal has reached 12 months of age. The growth plate in the distal 3rd metacarpal is said to be closed at approximately 6 months of age, and the proximal aspect of the proximal phalanx is closed by approximately 12 months of age (Figure 7).At this point any deviation must be compensated for and, may incur uneven wear and strain on the joint and its tissues for the rest of the animal’s days.

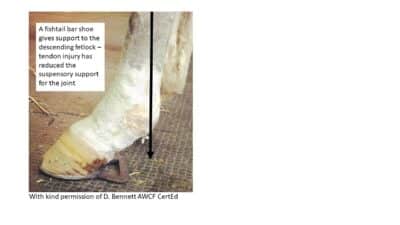

When looking at the angle formed by the joint from the lateral aspect, the overall conformation (including the angle of the shoulder and the length of the pasterns) will have an influence on the pressures placed on the joint. In a horse with long pasterns and a sloping shoulder, the weight will fall well behind the hoof capsule placing greater strain on the suspensory apparatus. As long as the foot balance is appropriate to the animal above it there are limits to what support can be given to the joint. Extreme examples of ‘support’ tend only to be practical when an injury has occurred and treatment is required (Figure 8).

In a well conformed limb the weight will fall centrally through the joints, loading both medial and lateral sides almost evenly -– although it is accepted that more body weight falls medially being closest to the horses’ centre of gravity. The effect of this can be seen in the thicker medial walls of the 3rd metacarpal and the larger medial condyle. If allowed to develop in an appropriate manner the bones, articular cartilage and supportive tissues will develop to be thickest or strongest at the points of most wear or load and, will adapt to sensible training. Even well conformed limbs will suffer joint issues if training is excessive or repetitive beyond the ability of biology to adapt, likely resulting in a lame horse.

When the well conformed limb is observed moving towards (frontal plane) or away from you, the joint should appear to descend centrally over the hoof capsule (Figure 9).

“Even well conformed limbs will suffer joint issues if training is excessive or repetitive beyond the ability of biology to adapt, likely resulting in a lame horse”

This means all the structures that are taking load or strain are sharing it evenly with no one aspect being overloaded or loaded suddenly. From the lateral aspect the well conformed limb presents a joint that is not so upright that shock cannot be adequately taken by the soft tissue or, so sloping that the soft tissues have an excessive load placed upon them even at low speed. This can be very subjective according to breed or type but 50-55° is considered ‘normal’.

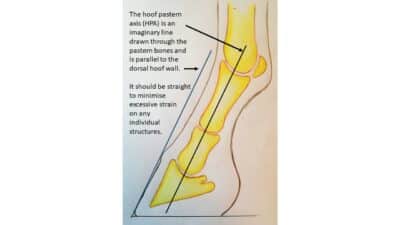

However a straight hoof pastern axis (HPA) is the goal of the hoof care professional (Figure 10). A limb that presents with either a broken forward or back HPA, will have excessive strain placed on either the bones and cartilage (broken forward) or the soft tissue (broken back) of the joint.

Signs of damage in the joint can occur before lameness is present and may be considered ‘blemishes’ such as windgalls, but they are a warning sign that the joint is experiencing excessive strain.

Repetitive strain may result in a lame horse and, can be loosely classified by the tissues it is associated with:

- Bone damage -– such as fractures.

- Articular cartilage – this can be a developmental issue such as Osteochondrosis (OCD) or a degenerative problem such as degenerative joint disease (DJD).

- Synovial structures – for example windgalls are either articular (joint capsule) or tendinous (tendon sheath) and are caused by extra synovial fluid being produced as part of an inflammatory reaction.

- Ligament damage – modern diagnostic methods such as MRI allow close examination of the ligaments. Collateral ligament damage due to uneven footfall and loading has become quite commonly diagnosed as a cause of lameness. More obvious issues are sprains, tears or ruptures to the suspensory ligament or one of its branches. In older horses or those in disciplines requiring extreme hindlimb loading, like high level dressage, suspensory desmitis is becoming more common and, can result in a general breakdown in the suspensory apparatus; the fetlocks are seen to ‘sag’ closer to the ground.

- Tendon damage – damage to these structures most commonly occurs between the carpus (knee) and the fetlock but can occur in the region of the joint.

- Joint luxation (lateral/medial plane) or subluxation (dorsal/palmar plane) is less common but seen in high speed activities or from traumatic injury e.g. from a horse putting a foot down a hole at speed.

- In young growing horses epiphysitis (enlargement of the growth plate) can create swelling and pain in the fetlock region.

When considering all the activities our equines participate in and, given the architecture of this amazing joint – it is one excellent example of the resilience of the equine form. Care should be taken to allow correct and steady development of the skeleton and, consideration given to its supporting structures, so that it can remain strong and healthy throughout its working life.

Glossary of common terms

- Deep – furthest away from the surface

- Distal – Away from the body

- Dorsal – Towards the spine or on a limb the front of the leg

- Lateral – Away from the midline

- Medial – towards the midline Palmar – Back surface of lower forelimb (Plantar in hind)

- Proximal – Towards the body Superficial – closest to the surface

Suggested further reading

Farriery: The whole horse concept, David Gill ISBN 978-1-904761-55-6

Horse movement, structure function and rehabilitation, Gail Williams ISBN: 978-1-908809-11-7