Diseases & Conditions, Featured, Strangles

Strangles in horses – what happens?

Helen Whitelegg Senior Campaigns Officer at Redwings, describes this highly infectious disease

Strangles in horses is a unique disease, not only in how it infects and passes between them but, in the practical challenges an outbreak presents for owners and yard managers, in addition to often considerable financial and emotional costs. However, thanks to persistent research, we have never been better placed to prevent, manage and even eradicate strangles. With an estimated 600 outbreaks still affecting UK horses every year, now is the time to rethink our knowledge, attitudes and behaviour around strangles and recognise it as a risk we all face, and that we can all do something about.

How is strangles in horses contracted?

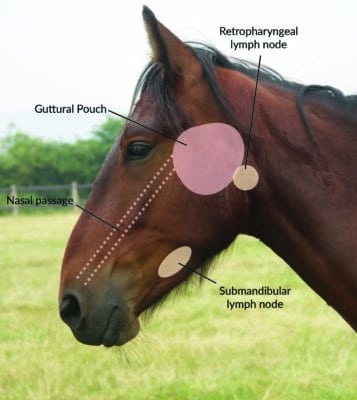

Strangles develops when a horse is infected with streptococcus equi bacteria. Their first goal is to enter the respiratory system, usually via the nasal passages. Strangles is not an airborne disease, and nose-to-nose contact between horses is the most effective means of transmission. However, the bacteria have some ability to survive in the environment, meaning a horse could pick up infection indirectly through contact with contaminated surfaces, equipment, water sources, or even human hands and clothing.

Research has shown that the bacteria do not live for more than two to three days in hot, dry conditions, especially if exposed to direct sunlight. But in cooler, wetter conditions such as a damp bucket in winter, live bacteria can be detected more than a month after the item was contaminated. Bacteria are known to survive in a water tank for as long as six weeks after being visited by an infected horse. On entering the horse’s respiratory system, bacteria make their way to one or more of the nearest lymph nodes. Here they are well-hidden, meaning that diagnostic tests are of little use in detecting infected horses during the incubation period (the time from contact with bacteria to first signs of ill-health). Not all horses will become sick through exposure to streptococcus equi bacteria.

The quantity of bacteria taken in is an important factor, along with the horse’s immune capability. An individual who has had strangles in the past and is exposed to a smaller bacterial load is more likely to fight off infection, or only show mild symptoms (though they can still infect other horses). A ‘naive’ horse, whose immune system has not dealt with strangles before, and who receives a substantial dose of bacteria is almost certain to be hit hard by the disease.

Clinical signs

A horse’s immune status and the bacterial quantity also affect how quickly disease progresses. Incubation is usually between two and 14 days, but can be as long as 21 days. The first clinical signs are likely to be fever (a temperature over 38.5oc) and being off-colour. At this point, the horse is not usually infectious to other horses, making it the ideal time to spot and contain the disease. Regular temperature-checking and using quarantine as a precaution are two important habits that all horse-owners can develop to help them stay a step ahead of infectious disease.

As infection develops, we may see signs such as thick nasal discharge, swollen glands and abscesses forming where lymph nodes are located (behind the cheek, under the jaw and/or around the eyes). The horse may also have a sore throat, making them reluctant to eat, and some patients present with a cough. In many cases the horse will feel extremely unwell and veterinary support and good patient care are crucial.

Each retropharyngeal lymph node is adjacent to one of the guttural pouches. Abscesses in these lymph nodes commonly burst into the pouch, releasing pus into the fist-sized space it offers.

The only route out of the guttural pouch is through a small flap and down the horse’s nasal passage. The nasal discharge we often see with strangles is in fact draining pus. Most horses make a full recovery from strangles within a few weeks.Fatalities are not common but, the disease is life-threatening in serious cases, with horses who are young, elderly or have other health conditions being most at risk.

It is vital to remember that horses are likely to remain infectious after clinical symptoms have resolved, for up to two months. To prevent further spread of bacteria, horses must test negative for strangles before leaving quarantine.

Complications

Strangles can lead to complications, though most presentations are thankfully rare. At Redwings, our very small number of strangles fatalities were due to the condition ‘bastard strangles’, where infection moves beyond the respiratory system to other parts of the horse’s body. Abscesses in the abdomen, lungs, brain and mammary glands have been recorded. Without visible signs of abscessation, bastard strangles is difficult to diagnose and the prognosis is poor.

A far more common complication, are cases where not all pus drains from the guttural pouch. Instead, it congeals and finally becomes solid ‘pebbles’ of dried pus called chondroids. Strangles bacteria can continue to live in chondroids long after clinical disease has passed, and the horse appears perfectly healthy. These horses are now strangles carriers, and may remain so indefinitely.

Carriers are not consistently infectious but, could discretely shed bacteria at any time to infect other horses without any indication that they are the source of disease. Thankfully, we can not only identify and treat strangles carriers, but with targeted outbreak management, we can prevent their development in the first place.

Read more about strangles here

To find out more, watch Redwings’ short animation ‘How does a horse become a strangles carrier?’